In a recent analysis conducted by the Westwood Global Energy Group, a promising future shines on Nigeria’s oil and gas sector after a decade of untapped potential. The nation’s success, however, hinges on the timely completion of projects, alongside improvements in nationwide infrastructure and security.

With a freshly elected president at the helm, Nigeria sets its sights on ramping up crude production from the 1.3 million barrels per day (bpd) recorded in 2022 to an ambitious 2.6 million bpd by 2027. The goal is to capitalize on the energy deficits witnessed in Europe and the burgeoning hydrocarbon demand from rapidly industrializing countries like China and India.

Yet, Westwood’s analysis paints a cautious picture, indicating that under the current circumstances, Nigeria’s liquid production may not surpass 1.9 million bpd by 2030. Even with several significant offshore projects on the horizon, the nation is projected to hit the 2.6 million barrels of oil equivalent per day (boepd) milestone by 2030 only if projects progress as planned—a historical rarity. Alarmingly, data suggests that any further delays could inflict lasting damage on Nigeria’s production aspirations.

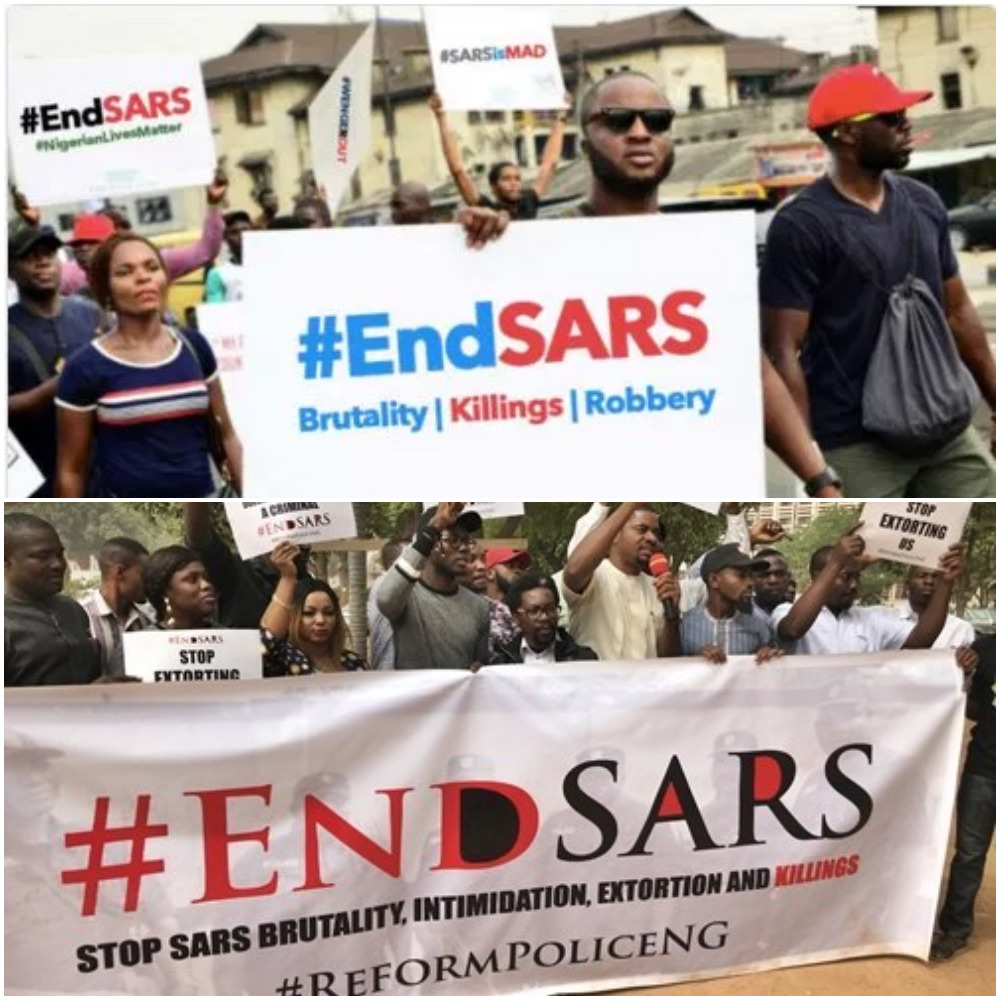

Addressing this situation, Michela Francisco, the Onshore Energy Analyst at Westwood, highlighted Nigeria’s historical role as Africa’s primary oil producer. However, the past decade has seen setbacks in upstream capital expenditure, security instability, and oil theft. Optimism now swirls around revitalizing Nigeria’s oil and gas sector. While progress has been initiated, Michela emphasized that the nation must continue creating an enticing business environment to attract local and international energy companies, a crucial step for the expected success.

In the later months of 2022, the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) made waves by announcing a mini-exploratory bid round for seven ultradeep offshore blocks. Following the bidding process in January 2023, Westwood forecasts an annual average of 140 development wells to be drilled up until 2030, stemming from these new discoveries. The potential outcome is an escalation in production beyond the current projections.

Building on this notion, Michela asserts that while Nigeria might not be on track to achieve its set targets just yet, the country is undeniably taking substantial strides to reshape its oil and gas industry, harnessing the potential of its abundant reserves. The impending years are deemed a pivotal juncture for domestic oil companies to seize the lead in onshore and shallow water exploration, possibly heralding an upswing in their fortunes.

As Nigeria’s oil and gas sector embarks on this transformative journey, stakeholders must remain vigilant about overcoming hurdles like project delays, security concerns, and infrastructure limitations. Timely project execution will prove to be the linchpin, determining whether Nigeria can effectively tap into its newfound potential and emerge as a significant player in the global energy landscape. With the right strategy and steadfast commitment, the nation could well chart a course toward achieving its aspirations and solidify its position as a key contributor to the world’s energy needs.